Introduction Link to heading

Varint is a widely recognized technique used for compressing integer streams. Essentially, it suggests that it can be more efficient to encode a number using a variable-length representation instead of a fixed-size binary representation. By removing leading zeros from the binary number, the overall representation size can be reduced. This technique works particularly well for encoding smaller numbers.

In this article, I provide a brief introduction and rationale for varint encoding. Additionally, I describe the Stream VByte format, which enables fully vectorized decoding through SSSE3 instructions. I also share my findings from implementing this algorithm in Rust, which includes both encoding and decoding primitives and the ability to read data from both RAM and disk.

Algorithm was tested on several platforms:

| CPU | Base Freq. (GHz) | Turbo Freq. (GHz) | Result (GElem/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xeon E3-1245 v5 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 5.0 |

| Core i7-1068NG7 | 2.3 | 4.1 | 5.5 |

The decoding speed is 0.75 CPU cycles per integer on average.

Motivation Link to heading

Varint compression is widely used in various contexts:

- It is utilized in serialization formats to achieve more efficient state transfer representation. For example, Protobuf employs varint compression.

- Database engines often employ varint compression (for example, SQLite BTree page format).

- Search engines heavily rely on varint compression to compress document lists that contain IDs of documents where a specific word is present (referred to as posting lists).

- It can be argued that UTF8 is a form of varint encoding. However, it is a special variant crafted to maintain compatibility with the binary representation of ASCII text.

Despite its success, varint compression faces a specific challenge: slow decoding speed. To comprehend the reason behind this, it is necessary to understand how classical varint encoding functions.

Scalar varint Link to heading

In traditional varint encoding, the most significant bit of each byte is reserved to indicate whether the byte is a continuation of the previous byte. The remaining bits carry the actual number.

Here’s how numbers are encoded:

- Numbers that can fit within 7 bits (excluding leading zero bits) are encoded as

0xxxxxxx. - Numbers with 14 bits are encoded as

0xxxxxxx1xxxxxxx. - Numbers with 21 bits are encoded as

0xxxxxxx1xxxxxxx1xxxxxxx, and so on. - A 32-bit number in this scheme would be encoded as 5 bytes:

0000xxxx1xxxxxxx1xxxxxxx1xxxxxxx1xxxxxxx.

However, this approach introduces a significant data dependency in the format. Decoding the next number can only begin after decoding the previous number because the offset where the next number starts in the byte stream needs to be determined. As a result, instructions cannot be executed in parallel on modern CPUs, hindering performance.

Stream VByte Link to heading

Varints decoding can be vectorized using various methods, including the patented varint-G8IU. One elegant solution, in my opinion, is the Stream VByte format proposed by Daniel Lemire, Nathan Kurzb, and Christoph Ruppc.

The approach is as follows: we separate the length information and the number data into independent streams, allowing us to decode a group of numbers in parallel.

Consider this observation: for a u32 number, there are four possible lengths in bytes. These lengths can be represented using 2 bits (00 for length 1, 11 for length 4). Using 1 byte, we can encode the lengths of four u32 numbers. We refer to this byte as the “control byte”. The sequence of control bytes forms the control stream. The second stream, called the data stream, contains the bytes of the compressed varint numbers laid out sequentially without any 7-bit shenanigans.

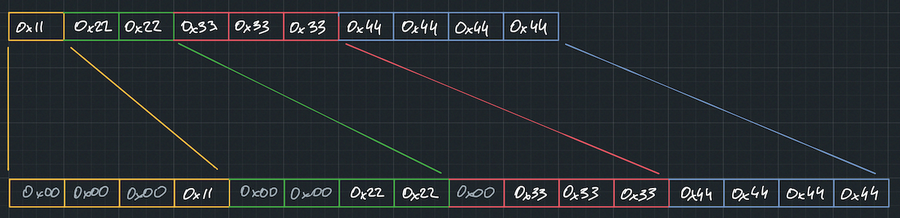

Let’s take an example. Suppose we encode the following four numbers: 0x00000011, 0x00002222, 0x00333333, and 0x44444444. In the encoded format, they would appear as follows:

CONTROL STREAM:

0x27 <- 00_01_10_11 – lengths 1, 2, 3 and 4 respectively

DATA STREAM:

0x11, 0x22, 0x22, 0x33, 0x33,

0x33, 0x44, 0x44, 0x44, 0x44

Now, we can read a single control byte, decode the lengths of four u32 numbers, and decode them one by one. This already represents an improvement over the original scalar decode implementation. However, we can achieve even greater performance. In fact, we can decode all four numbers in just one CPU instruction!

If we consider it carefully, all we need to do is insert zeros in the appropriate positions to align the numbers correctly.

And there is instruction for that.

PSHUFB SSSE3 instruction Link to heading

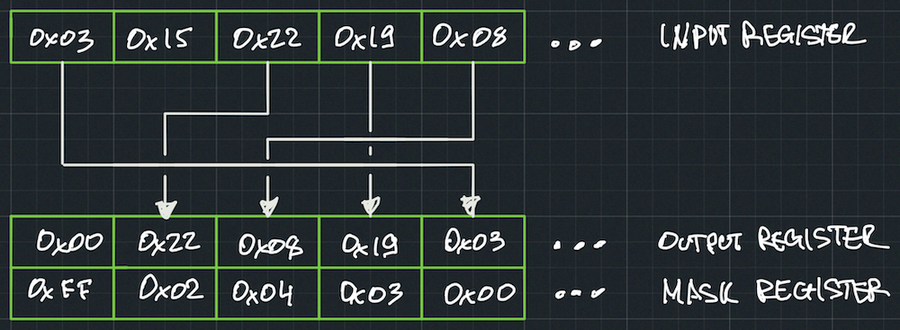

The PSHUFB instruction offers more flexibility than just inserting zeros. It allows you to permute or zero out bytes within a 16-byte register in any desired arrangement.

PSHUFB operates on two 16-byte registers (__m128): an input register and a mask register, producing a 16-byte register output. Each byte in the output register is controlled by the corresponding byte in the mask register. There are two possible scenarios:

- If the most significant bit (MSB) of a byte in the mask register is set, the corresponding byte in the output register will be zeroed out.

- If the MSB is not set, the lower 4 bits of the byte in the mask register indicate which byte from the input register should be copied to the output.

This instruction provides a powerful mechanism for manipulating and rearranging bytes within registers.

When decoding four numbers in parallel, it is necessary to provide a mask that ensures each number byte is placed in its corresponding position within the output register. By carefully configuring the mask, we can decode all four u32 numbers in a single CPU instruction. This approach maximizes efficiency and allows for significant performance gains.

How to create mask? Link to heading

An interesting aspect of this algorithm is that there is no need to compute the masks at runtime. Since there are only 256 possible masks that cover all the potential length variations of four encoded numbers, these masks can be precomputed during compilation and stored in an array. Accessing the appropriate mask becomes a simple task of using the control byte as an index in the array. Rust’s const fn feature is particularly useful for this purpose, as it allows for the efficient computation and storage of the masks during the compilation phase.

Implementation details Link to heading

Ok, more to the Rust implementation. Decode kernel is very simple.

1type u32x4 = [u32; 4];

2

3const MASKS: [(u32x4, u8); 256] = ...

4

5fn simd_decode(input: *const u8, control_word: *const u8, output: *mut u32x4) -> u8 {

6 unsafe {

7 let (ref mask, encoded_len) = MASKS[*control_word as usize];

8 let mask = _mm_loadu_si128(mask.as_ptr().cast());

9 let input = _mm_loadu_si128(input.cast());

10 let answer = _mm_shuffle_epi8(input, mask);

11 _mm_storeu_si128(output.cast(), answer);

12

13 encoded_len

14 }

15}

- Line 7: Reads the shuffle mask and encoded length from the statically precomputed array.

- Lines 8-9: The input and masks are loaded into

__m128iregisters. It’s important to note that all loads and stores must be unaligned, hence the use ofstoreu/loadu. If you attempt to load an unaligned address using the_mm_load_si128intrinsic, you may encounter a segmentation violation error. - Line 10: Restores the proper boundaries of four

u32numbers. - Line 11: The numbers are stored in the result buffer.

- Line 13: Returns the number of consumed bytes from the data stream. In the next iteration, the data stream will need to advance by this amount of bytes.

Now we can utilize this kernel to decode any number of integers.

pub struct DecodeCursor {

elements_left: usize,

control_stream: *const u8,

data_stream: *const u8,

}

fn decode(&mut self, buffer: &mut [u32]) -> io::Result<usize> {

/// Number of decoded elements per iteration

const DECODE_WIDTH: usize = 4;

assert!(

buffer.len() >= DECODE_WIDTH,

"Buffer should be at least {} elements long",

DECODE_WIDTH

);

if self.elements_left == 0 && self.refill()? == 0 {

return Ok(0);

}

let mut iterations = buffer.len() / DECODE_WIDTH;

iterations = iterations.min((self.elements_left + DECODE_WIDTH - 1) / DECODE_WIDTH);

let decoded = iterations * DECODE_WIDTH;

let mut data_stream = self.data_stream;

let mut control_stream = self.control_stream;

let mut buffer = buffer.as_mut_ptr() as *mut u32x4;

for _ in 0..iterations {

let encoded_len = simd_decode(data_stream, control_stream, buffer);

data_stream = data_stream.wrapping_add(encoded_len as usize);

buffer = buffer.wrapping_add(1);

control_stream = control_stream.wrapping_add(1);

}

self.control_stream = control_stream;

self.data_stream = data_stream;

let decoded = decoded.min(self.elements_left);

self.elements_left -= decoded;

Ok(decoded)

}

As you can see, this code heavily relies on pointers, and there is a good reason for it - performance.

Performance Considerations Link to heading

The initial implementation of this code was only able to decode around 500 million integers per second. This is significantly slower than what the CPU is capable of! There are some tricks that can be implemented to utilize the CPU more effectively. Let me explain what you need to pay attention to.

Use the correct intrinsics Link to heading

In the initial implementation of the decode kernel, I used _mm_loadu_epi8() instead of _mm_loadu_si128(). It turns out that _mm_loadu_epi8() is part of the AVX512 instruction set, not the SSSE3 ISA. Surprisingly, the program didn’t fail and passed all the tests. It turns out, the Rust library contains retrofit implementations that are used when the target CPU doesn’t support certain instructions. As you might guess, these retrofit implementations are not nearly as fast.

Lesson 1: Always check if the intrinsic you are using is supported on the target CPU.

Investigate potential issues with slice indexing Link to heading

Another issue to consider is that slice indexing can generate a significant number of branch instructions. When indexing slices, the compiler is forced to check the slice boundaries each time the slice is accessed. Consider the following code snippet:

pub fn foo(x: &[i32]) -> i32 {

x[5]

}

it translates to the following assembly:

example::foo:

push rax

cmp rsi, 6

jb .LBB0_2

mov eax, dword ptr [rdi + 20]

pop rcx

ret

.LBB0_2:

lea rdx, [rip + .L__unnamed_1]

mov edi, 5

call qword ptr [rip + core::panicking::panic_bounds_check@GOTPCREL]

ud2

In the code snippet provided, we can observe that the first action performed by the compiler is to check the slice bounds (cmp rsi, 6). If the value is below 6, core::panicking::panic_bounds_check() is called. It is a safety measure implemented by the compiler, and there’s no doubt about its necessity. However, these conditional jumps significantly impact performance. Therefore, in tightly optimized loops, it is preferable to replace slice indexing with a more efficient alternative.

The question then arises: What should it be replaced with? The first option that comes to mind is using iterators (iter()). However, I haven’t been able to come up with an elegant solution using Rust iterators, primarily because the data stream needs to be advanced by a different number of bytes in each iteration. Another possibility is to use slice::get_unchecked(), but I strongly discourage its usage.

A better approach, in this case, is to employ pointer arithmetic while ensuring as much safety as possible. Most pointer operations are safe by themselves, but dereferencing them can lead to SIGSEGV errors.

Nevertheless, as always, the first step is to determine if this is indeed a problem in the given scenario. Let’s consider the previously shown code snippet:

const MASKS: [(u32x4, u8); 256] = ...

fn simd_decode(input: *const u8, control_word: *const u8, output: *mut u32x4) -> u8 {

unsafe {

let (ref mask, encoded_len) = MASKS[*control_word as usize];

...

}

}

In this case, the compiler can generate assembly code without any additional checks because it has certain knowledge:

MASKSis an array of size 256.*control_wordis strictly less than 256 (u8).

Lesson 2: Slice access often involves branching, which can negatively impact performance. When optimizing code within tight loops, it is important to minimize the use of slice indexing and replace them with iter() where possible.

Check your loops Link to heading

Despite all the optimizations mentioned earlier, the performance remained at around 2.5 billion integers per second. The technique that significantly improved performance was loop unrolling. This is similar to the concept discussed in the article “How fast can you count to 16 in Rust?”. By minimizing the number of branches per unit of work, we can achieve better performance. But you need to nudge the compiler a little bit.

const UNROLL_FACTOR: usize = 8;

while iterations_left >= UNROLL_FACTOR {

for _ in 0..UNROLL_FACTOR {

let encoded_len = simd_decode(data_stream, control_stream, buffer);

data_stream = data_stream.wrapping_add(encoded_len as usize);

buffer = buffer.wrapping_add(1);

control_stream = control_stream.wrapping_add(1);

}

iterations_left -= UNROLL_FACTOR;

}

Now, I’m going to show you the assembly code that this source translates into. Please pay attention to the absence of any branching instructions, rather than focusing on the individual instructions themselves.

movzbl (%rsi), %eax

leaq (%rax,%rax,4), %rax

movzbl 0x10(%r11,%rax,4), %r12d

vmovdqu (%r8), %xmm0

vpshufb (%r11,%rax,4), %xmm0, %xmm0

vmovdqu %xmm0, (%rbx,%r13,4)

leaq (%r8,%r12), %rax

addq %r12, %rdx

movzbl 0x1(%rsi), %ecx

leaq (%rcx,%rcx,4), %rcx

movzbl 0x10(%r11,%rcx,4), %r15d

vmovdqu (%r8,%r12), %xmm0

vpshufb (%r11,%rcx,4), %xmm0, %xmm0

vmovdqu %xmm0, 0x10(%rbx,%r13,4)

movzbl 0x2(%rsi), %ecx

leaq (%rcx,%rcx,4), %rcx

movzbl 0x10(%r11,%rcx,4), %r8d

vmovdqu (%r15,%rax), %xmm0

addq %r15, %rax

vpshufb (%r11,%rcx,4), %xmm0, %xmm0

vmovdqu %xmm0, 0x20(%rbx,%r13,4)

addq %r8, %r15

addq %r15, %rdx

movzbl 0x3(%rsi), %ecx

leaq (%rcx,%rcx,4), %rcx

movzbl 0x10(%r11,%rcx,4), %r15d

vmovdqu (%r8,%rax), %xmm0

vpshufb (%r11,%rcx,4), %xmm0, %xmm0

vmovdqu %xmm0, 0x30(%rbx,%r13,4)

addq $0x4, %rsi

addq %r15, %r8

addq %rax, %r8

addq %r15, %rdx

leaq 0x10(%r13), %rax

addq $-0x4, %r9

cmpq $0x4, %r9

Isn’t it a beauty? The whole inner loop is implemented as one long highway, if you will, with no exit lanes or splits. Only arithmetics and vector operations of different kinds. Next instructions and memory accesses are easily predictable. Therefore, the CPU can prefetch all required data in time.

And the result is 5.5 billion integers per second, which is quite remarkable for a 4.1GHz CPU if you ask me.

The outcome of this optimized implementation is the ability to process an 5.5 billion integers, which is impressive considering the clock speed of the CPU, which stands at 4.1GHz.

$ cargo bench -q --bench decode

decode/u32 time: [89.660 µs 90.267 µs 90.930 µs]

thrpt: [5.4988 Gelem/s 5.5391 Gelem/s 5.5767 Gelem/s]

change:

time: [-1.0102% +0.5065% +2.2278%] (p = 0.54 > 0.05)

thrpt: [-2.1792% -0.5040% +1.0205%]

No change in performance detected.

Found 8 outliers among 100 measurements (8.00%)

6 (6.00%) high mild

2 (2.00%) high severe

Further optimizations Link to heading

There are some additional enhancements that can be applied to this code, which I am eager to try:

- We can eliminate some unaligned loads within the kernel. Although on an x86 platform, this may not yield significant benefits due to its memory model, it might be advantageous on ARM. But ARM kernel should be written first.

- Currently, the length of encoded quadruplets is memoized in the same manner as the masks. However, it is possible to compute the length of the encoded quadruplet in runtime. This optimization pays off when decoding not just a single control word, but four of them at once (as a

u32).

Conclusion Link to heading

Varint is a simple, powerful, and widely used compression algorithm. Without this type of compression, fast search engines like Apache Lucene or Tantivy would be impractical. When working with uncompressed data, memory bandwidth quickly becomes a bottleneck. However, in its basic implementation, varint is unable to fully utilize modern CPUs due to data dependencies. Stream VByte addresses this issue by separating length and data information, allowing independent reading of both streams and enabling the pipelining of the decoding algorithm.