Introducton Link to heading

Binary search is a very fast algorithm. Due to its exponential nature, it can process gigabytes of sorted data quickly. However, two problems make it somewhat challenging for modern CPUs:

- predictability of instruction flow;

- predictability of memory access.

At each step, binary search splits the dataset into two parts and jumps to one of those parts based on a midpoint value. It’s difficult for the CPU to predict which parts of the presumably large array will be accessed in the next iteration. As a result, binary search produces many cache misses, which stalls the CPU pipeline, resulting in poor instruction-per-clock performance.

Let’s try to find a way to address these problems. But first, let’s establish a performance baseline using the slice::binary_search() method with a Vec<u32> of different sizes.

This graph shows the average time it took to look up a random element in an array of different sizes. Graph also shows the size of L1/L2/L3 CPU caches test was run on (sources).

- Intel Core i7-1068NG7 CPU @ 2.30GHz

- 32Gb LPDDR4X 3733 MHz

- Darwin Kernel Version 22.4.0

In practical terms, the performance of binary search starts to drop when the dataset becomes larger than the size of the on-core cache (L2), which in my case is 512KB or 128K u32 elements.

Eytzinger Layout Link to heading

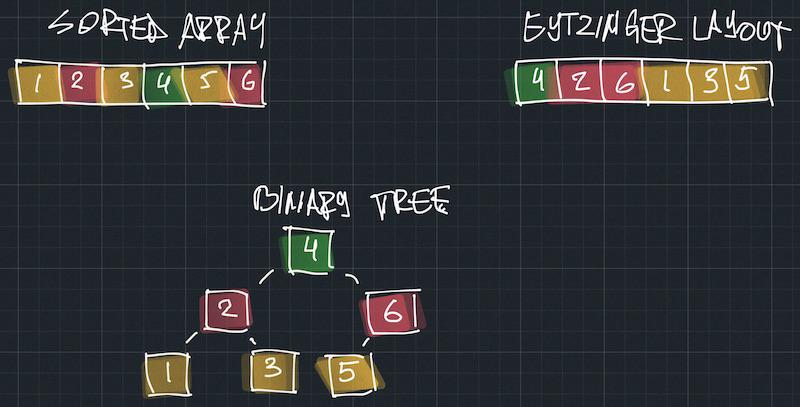

One way to address the memory access predictability problem is to use the Eytzinger layout. It’s a method of storing sorted data so that elements at the same tree depth are stored together. Let’s illustrate this idea.

The array starts with the tree root (depth=0), followed by all the elements at depth 1, then depth=2, and so on. Using this layout, tree siblings are always stored together in memory, which means there are fewer cache misses.

This layout requires array preprocessing, so it’s appropriate when the underlying array is fixed or changes infrequently. The Eytzinger layout is only applicable if you don’t need sorted data as the output of the algorithm. An appropriate use case for this layout would be when you only need to test the presence of an element in an array.

I won’t delve deeply into the algorithm of constructing such an array, but you can check the sources or read [1].

Although it might seem quite complex, navigating an Eytzinger layout array is simple if you store all your elements starting from index 1 (the first element is a dummy). You just update the index to idx = 2 * idx if you want to go left or idx = 2 * idx + 1 if you want to go right:

pub fn binary_search(data: &[u32], value: u32) -> usize {

let mut idx = 1;

while idx < data.len() {

let el = data[idx];

if el == value {

return idx;

}

idx = 2 * idx + usize::from(el < value);

}

0

}

We don’t need to maintain array search boundaries anymore!

Let’s benchmark this code against standard binary search.

It’s interesting to note that when the dataset is small enough to fit in cache, Eytzinger can provide significant performance gains. However, everything changes when we hit main memory.

Branchless Eytzinger implementatation Link to heading

Let’s try another idea, but first, let’s check the assembly of our eytzinger implementation

1example::eytzinger_binary_search:

2 cmp rsi, 2

3 jb .LBB0_4

4 mov eax, 1

5.LBB0_2:

6 cmp dword ptr [rdi + 4*rax], edx

7 je .LBB0_5

8 setb cl

9 movzx ecx, cl

10 lea rax, [rcx + 2*rax]

11 cmp rax, rsi

12 jb .LBB0_2

13.LBB0_4:

14 xor eax, eax

15.LBB0_5:

16 ret

The loop body (highlighted lines 6-12) contails two branches:

cmp+jbon lines 11-12 are the loop invariant –idx < data.len();cmp+jeon lines 6-7 checks if we found the target element, If we do, we jump to.LBB0_5, where the return from the function is executed

We can’t do anything about the first branch, but we can actually eliminate the second one.

This is where the exponential nature of binary search comes in handy. In practice, it can be more beneficial not to check if we found the target element in a loop body and instead traverse the whole tree down to the leaves anyway. Yes, there will be some extra iterations, but not many, because binary search has a complexity of O(log n).

pub fn binary_search_branchless(data: &[u32], target: u32) -> usize {

let mut idx = 1;

while idx < data.len() {

let el = data[idx];

idx = 2 * idx + usize::from(el < target);

}

idx >>= idx.trailing_ones() + 1;

usize::from(data[idx] == target) * idx

}

The last two lines of code are worth some attention, as they decode the index of a found element.

How the found element index is decoded? Link to heading

It might not be obvious how the following code is decoding the index of the target element (if any). So let’s take a closer look.

idx >> (idx.trailing_ones() + 1)

usize::from(data[idx] == target) * idx

Decoding code relies on the following facts:

- following two expressions are equivalentFrom this, you can conclude that

// arithmetic index update idx = 2 * idx + usize::from(el < target); // binary operation index update idx = (idx << 1) | usize::from(el < target);idxcan be interpreted as a binary tree traversal history, where each bit is 1 if we took a right turn and 0 if we took a left one. For example, a value of 19 (0001_0011) after 5 iterations means that the sequence of turns was: RLLRR. - if we found the target element we will make a left turn

usize::from(el < value) == 0 - when we make a left turn (in context of

el == value) we end up in part of the tree where all elements less than the target. Therefore, all subsequent turns will be right turns.

(1) means that you can revert the effect of an arbitrary number of iterations just by shifting idx to the right. (3) means that the required number of iterations you need to revert is the number of trailing ones in idx. The “off by one” is to cancel out the iteration where the target element was found (we’re interested in the value of idx before the iteration completed).

After this manipulation, idx will point at the least element in the array greater than or equal to target or zero if there is no such element. Now we only need to check this element against the target. We can do it with the following code:

// naive solution

if data[idx] == target { idx } else { 0 }

// branchless solution

usize::from(data[idx] == target) * idx

Let’s benchmark branchless version of the code against previous implementations

The branchless Eytzinger algorithm is faster than the branchy one, but on large datasets, the standard binary search outperforms both of those algorithms.

Branchless Eytzinger with memory prefetch Link to heading

Although the Eytzinger layout memory access is very predictable, on large arrays, memory access still dominates the overall running time. The slope of the Eytzinger layout changes drastically when the algorithm is forced to go to the main memory.

Let’s add software memory prefetch. We know that the next iteration will always require consecutive elements of an array: 2 * idx or 2 * idx + 1. This allows us to instruct the CPU about the data we will need on the next iteration.

pub fn binary_search_branchless(data: &[u32], target: u32) -> usize {

let mut idx = 1;

while idx < data.len() {

unsafe {

let prefetch = data.as_ptr().wrapping_offset(2 * idx as isize);

_mm_prefetch::<_MM_HINT_T0>(ptr::addr_of!(prefetch) as *const i8);

}

let el = data[idx];

idx = 2 * idx + usize::from(el < target);

}

idx >>= idx.trailing_ones() + 1;

usize::from(data[idx] == target) * idx

}

As was pointed out on the Reddit methods like SliceIndex::get_unchecked() and ptr:add() are undefined behaviour even if the resulting reference is not dereferenced. But it follows from the documentation that ptr::wrapping_offset() is safe:

This operation itself is always safe, but using the resulting pointer is not.

We are not using the pointer (dereferencing), but pass it to the prefetcht0 instruction which is by documentation

is merely a hint and does not affect program behavior

In case of an invalid address or TLB error, the prefetch instruction will ignore the address. This allows us to do prefetch unconditionally, even on the last iteration when 2 * idx is pointing after the end of an array.

I must give a credit to a /u/minno who suggested ptr::wrapping_offset() solution.

Memory prefetching indeed helps the Eytzinger layout perform faster than standard binary search across a wide range of array sizes.

Conclusion Link to heading

The branchless Eytzinger layout is a great option if the data you are searching over is fixed and can be preprocessed to accommodate a faster memory access layout. Because it respects the characteristics of modern CPUs, it is basically one of the fastest ways to search in sorted data when implemented correctly.

Additionally, there are some further ideas like S-trees ([4]) or mixed layout ([2]) that you could try if you’re looking for the best binary search.

Related links Link to heading

- Eytzinger Binary Search, Algorithmica

- Array Layouts for Comparison-based Searching Paul-Virak Khuong and Pat Morin

- Control Hazard, Computer Architecture, Dr Ranjani Parthasarathi

- Optimizing Binary Search, CppCon 2022, Sergey Slotin