Introduction Link to heading

Suppose we need to write a function that computes the next set of numbers in a range and stores them in a slice, as shown below:

let pl = RangePl::new(1..12);

let mut buffer = [0u64; 4];

pl.next_batch(0, &mut buffer); // returns 4, buffer[..] = [1, 2, 3, 4]

pl.next_batch(0, &mut buffer); // returns 4, buffer[..] = [5, 6, 7, 8]

pl.next_batch(10, &mut buffer); // returns 2, buffer[0..2] = [10, 11]

pl.next_batch(10, &mut buffer); // returns 0, buffer not updated

Key factors:

- Most importantly, although the function can be called with a buffer of any length, it will most likely be called with a buffer of length 16. The reason for this is explained in the motivation secton.

- The integer type must be

u64. - The function writes the result in a slice and returns the number of values written.

- The caller can provide the next element to continue from. If this element is greater than the range end, the iteration stops.

- The code will be executed in a controlled server environment, and you may use any x86 ISA extension you can think of (e.g., AVX512). Therefore,

-Ctarget-cpu=nativeis allowed.

Motivation Link to heading

This form of iteration may seem strange at first (well, I guess it is 😀), but it’s the way search systems fetch data from inverted index posting lists (hence the name RangePl).

This simple form of iteration can be used to test the correctness of search algorithms as well as to stress-test some parts of those algorithms. For this reason, it would be useful for this iterator to be as fast as possible and to not affect the performance of the search algorithm as much as possible.

The ability to skip some elements is used when the algorithm knows that there is no need to check elements less than the target element.

The u64 type is generally not a good idea for such systems. The prevalent approach is to use a narrower type and assign private identifiers to documents. This also helps with posting list compression when using delta encoding. Unfortunately, the system I’m working on, due to idiosyncratic reasons, needs to use external IDs to address documents, so I’m forced to use u64.

Naive implementation Link to heading

For benchmarking purposes, we’ll use Criterion to check how fast we can iterate over RangePl(0..1000) with the following code:

let mut buffer = [0; 16];

while input.next_batch(&mut buffer) != 0 {}

black_box(buffer);

The testing machine is an Intel Core i7-1068NG7 CPU @ 2.30GHz with 4 cores, running Darwin 22.4.0.

Let’s start with a naive implementation.

struct RangePl {

next: u64,

end: u64,

};

impl RangePl {

fn next_batch(&mut self, target: u64, buffer: &mut [u64]) -> usize {

self.next = self.next.max(target);

let start = self.next;

if start >= self.end {

return 0;

}

let range_len = (self.end - self.next) as usize;

let len = range_len.min(buffer.len());

for i in 0..len {

buffer[i] = self.next;

self.next += 1;

}

len

}

}

time: [599.00 ns 603.90 ns 608.94 ns]

thrpt: [1.6406 Gelem/s 1.6543 Gelem/s 1.6678 Gelem/s]

The naive code generates about 1.65 billion numbers per second, which is just 1 number every 2.5 CPU cycles (at 4.0GHz). For a modern, vectorized, deeply pipelined CPU, this is kind of slow.

Why is it so slow? Link to heading

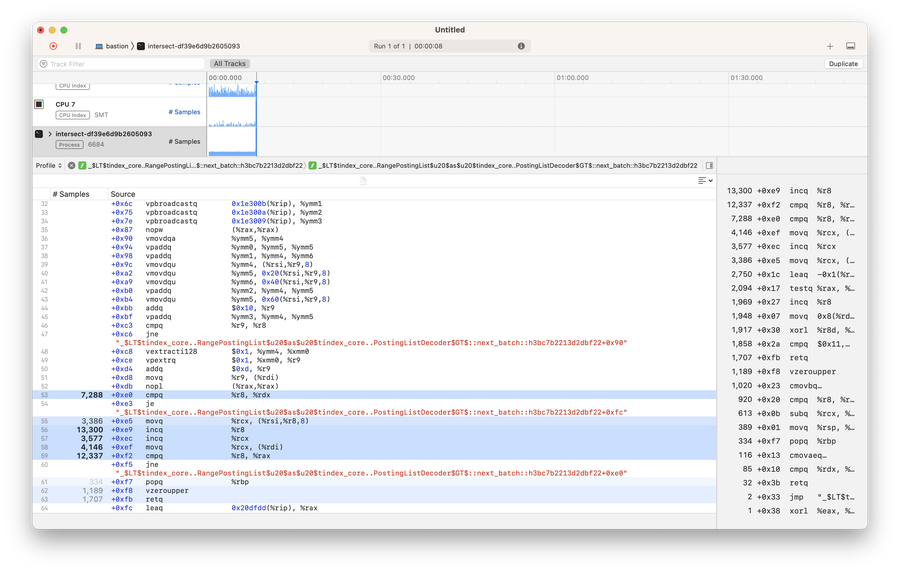

If we look at the instruction level profile, we’ll notice a strange thing. Although the compiler was able to vectorize this code, for some reason, the scalar implementation is being used.

It turns out the compiler produces code that uses the vectorized version only when there are 17 or more elements to process 🤦♂️.

cmp r8, 17

It would have been very handy if we needed to optimize our function for the 17-element buffer 😀. It would give us almost twice the performance. Unfortunately, this is not what we need.

time: [332.60 ns 334.71 ns 337.02 ns]

thrpt: [2.9642 Gelem/s 2.9847 Gelem/s 3.0036 Gelem/s]

change:

time: [-45.262% -44.641% -44.012%] (p = 0.00 < 0.05)

thrpt: [+78.609% +80.638% +82.687%]

Bargaining with a compiler Link to heading

I spent some time trying to convince the compiler that it should optimize the code for a particular buffer length. I found that if you chunk the buffer into pieces of 16 elements, the code will run about 60% faster.

for chunk in buffer[..len].chunks_mut(16) {

for item in chunk.iter_mut() {

*item = self.next;

self.next += 1;

}

}

time: [368.58 ns 370.77 ns 373.13 ns]

thrpt: [2.6774 Gelem/s 2.6944 Gelem/s 2.7104 Gelem/s]

Although it helps, the compiler only unrolls the loop by a factor of 4. Alright, let’s try to generate a different code path specifically for the 16-element case.

for chunk in buffer[..len].chunks_mut(16) {

if chunk.len() == 16 {

for item in chunk.iter_mut() {

*item = self.next;

self.next += 1;

}

} else {

for item in chunk.iter_mut() {

*item = self.next;

self.next += 1;

}

}

}

Note the identical code inside the if and else branches (DRY anyone? 😎). We will remove it later. It is only needed to provide the compiler with an additional degree of freedom to generate different code for the 16-element case.

Sadly, this won’t help much. At this point, I’ve started to suspect that maybe the compiler is having a hard time removing the loop dependency (e.g., self.next += 1). So, let’s remove it by using a predefined array of offsets. This constant array will be allocated statically and will not affect runtime performance:

const PROGRESSION: [u64; 16] = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15];

for chunk in buffer[..len].chunks_mut(PROGRESSION.len()) {

if chunk.len() == PROGRESSION.len() {

for (item, offset) in chunk.iter_mut().zip(PROGRESSION) {

*item = self.next + offset;

}

} else {

for (item, offset) in chunk.iter_mut().zip(PROGRESSION) {

*item = self.next + offset;

}

}

self.next += chunk.len() as u64;

}

This did indeed help to improve performance to some extent.

time: [321.99 ns 324.46 ns 326.79 ns]

thrpt: [3.0570 Gelem/s 3.0789 Gelem/s 3.1026 Gelem/s]

It’s interesting that the last two optimizations only work together. Implementing just one of them doesn’t change anything.

Let’s go nightly Link to heading

There is no way for the compiler to obtain the magic number 16 from the type system. This is partially why we are forced to jump through hoops. slice::chunk_mut() returns a slice of undefined size, so the compiler cannot reason about the slice length. This is where slice::as_chunks_mut() becomes very helpful (available in nightly). It forces you to provide a static chunk size and return slices of fixed-size arrays (and a reminder slice). This allows us to write:

const PROGRESSION: [u64; 16] = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15];

let (chunks, remainder) = buffer[..len].as_chunks_mut::<16>();

for chunk in chunks {

for (item, offset) in chunk.iter_mut().zip(PROGRESSION) {

*item = self.next + offset;

}

self.next += chunk.len() as u64;

}

for (item, offset) in remainder.iter_mut().zip(PROGRESSION) {

*item = self.next + offset;

}

self.next += remainder.len() as u64;

Hey, we are making progress!

time: [286.45 ns 289.37 ns 292.50 ns]

thrpt: [3.4154 Gelem/s 3.4523 Gelem/s 3.4875 Gelem/s]

In my opinion, this illustrates a very important point.

The compiler can only transform code in ways that it can prove to be safe. Therefore, a strict type system not only provides safety guarantees, but also allows the compiler to reason about code more freely and select more appropriate optimization strategies.

Unexpected surprise Link to heading

After experimenting with different approaches, I found a very simple code that works quite fast.

for i in buffer[..len].iter_mut() {

*i = self.next;

self.next += 1;

}

time: [267.90 ns 269.87 ns 271.90 ns]

thrpt: [3.6742 Gelem/s 3.7018 Gelem/s 3.7290 Gelem/s]

Wait, what?! If you’re wondering what the difference is between this code and the original naive approach, I’ll show the naive code one more time:

for i in 0..len {

buffer[i] = self.next;

self.next += 1;

}

Yes, it’s just the style of iteration. For whatever reason, when using the iter_mut() approach, the compiler selects a correct vector/scalar threshold of 16 elements, so the loop becomes vectorized.

Going wider Link to heading

Okay, we definitely cannot blame the compiler for not choosing the right threshold. But I don’t feel safe relying solely on the compiler for this. I would like to have code that can be transofrmed into fast assembly robustly. Besides, there is one more thing I noticed in the assembly code. Here is part of the loop body:

vpaddq ymm5, ymm0, ymm1

vpaddq ymm6, ymm0, ymm2

vmovdqu ymmword ptr [rdx + 8*r10], ymm0

vmovdqu ymmword ptr [rdx + 8*r10 + 32], ymm5

vmovdqu ymmword ptr [rdx + 8*r10 + 64], ymm6

vpaddq ymm5, ymm0, ymm3

vmovdqu ymmword ptr [rdx + 8*r10 + 96], ymm5

add r10, 16

vpaddq ymm0, ymm0, ymm4

ymm are 256-bit registers that are part of the AVX2 instruction set. Although I provided -Ctarget-cpu=native, and my CPU supports the AVX512, the compiler still doesn’t want to use it.

So, I decided to leave the general implementation to the compiler and write a 16-element specialization using the std::simd::u64x8 type (nightly only).

const PROGRESSION: u64x8 = u64x8::from_array([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]);

const LANES: usize = PROGRESSION.lanes();

const SPEC_LENGTH: usize = LANES * 2;

if buffer.len() == SPEC_LENGTH && (self.next + SPEC_LENGTH as u64) <= self.end {

// Specialization for 16 elements

let low = u64x8::splat(self.next) + PROGRESSION;

buffer[..LANES].copy_from_slice(low.as_array());

let high = low + u64x8::splat(LANES as u64);

buffer[LANES..].copy_from_slice(high.as_array());

self.next += SPEC_LENGTH as u64;

SPEC_LENGTH

} else {

// General case for slice of any size

let range_len = (self.end - self.next) as usize;

let len = range_len.min(buffer.len());

for chunk in buffer[..len].chunks_mut(8) {

// This code duplication is required for compiler to vectorize code

let len = chunk.len();

for (item, offset) in chunk.iter_mut().zip(0..len) {

*item = self.next + offset as u64;

}

self.next += len as u64;

}

len

}

There are some important aspects to this code:

- This code uses two

u64x8vectors to calculate the lower and higher parts of the resulting slice. - The control flow of the two variants is fully isolated. The 16-element specialization has its own return, and no code required for specialization is placed in the function prologue. This way, the compiler generates assembly code with fewer conditional jumps, which brings about a 10% improvement in performance.

Looking at the assembly code, we now see the usage of AVX512-related zmm registers in what resembles the body of our specialization.

vpbroadcastq zmm0, rsi

vpaddq zmm0, zmm0, zmmword ptr [rip + .L__unnamed_1]

vmovdqu64 zmmword ptr [rdx], zmm0

vpaddq zmm0, zmm0, qword ptr [rip + .LCPI0_2]{1to8}

vmovdqu64 zmmword ptr [rdx + 64], zmm0

mov eax, 16

mov qword ptr [rdi], rcx

vzeroupper

ret

And we get 6.5 GElem/s, which is a 4x speedup against the original code and 1.5 numbers per CPU cycle.

time: [150.12 ns 151.64 ns 153.21 ns]

thrpt: [6.5203 Gelem/s 6.5880 Gelem/s 6.6546 Gelem/s]

Conclusions Link to heading

So, how fast can you count to 16 in Rust? I guess the answer is about 10 CPU cycles. But this is not what it’s all about.

Modern compilers are good at two things: (1) not making stupid mistakes in assembly, and (2) writing assembly better than a human can on average. Unfortunately, they are not able to generate optimal assembly for every case, and it becomes harder with time because the computational model of modern hardware becomes more and more complex and less resembles programming models on which modern programming languages are built. So, I want leave you with the following advice:

- There is no way to know upfront which code will perform better. If you care about performance, benchmarking is the only way to go.

- There is no need to be able to write assembly. In most cases, the compiler will do it better than you. However, it is very important to be able to read assembly to ensure the compiler has indeed done its job.

- Rust, as well as C++, has done a great job of providing Zero Cost Abstractions. However, almost every abstraction is not transparent to the compiler in some way or another. It is important to be able to narrow down the set of applicable abstractions for a task and verify that the selected abstraction does not hinder performance.

If you think you know how to make this code even faster let me know.

Discussion of this post is on Reddit.